- Islamist groups in Sahel now pose major threat to Europe and rest of Africa.

- Strategic errors of Afghanistan and Libya combine to fuel new crisis.

- Weak and corrupt regional government allies offer no solution

From Afghanistan to the Sahel

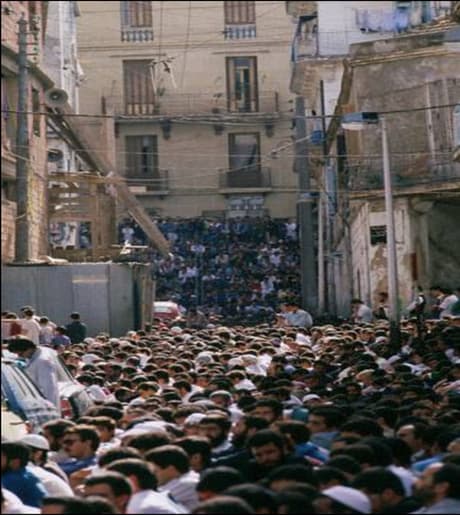

In the 1980s, each Friday the narrow streets around Al-Sunnah Mosque in the down at heel Bab El Oued district of Algiers were thronged with young men.

In their hundreds they flocked to hear firebrand imam Ali Belhadj denounce the government of the National Liberation Front (FLN), which has led Algeria since independence from France in 1962. He lambasted leftists, liberal reforms, politicians, France and the West, ‘the impious’ in general. Only Islam escaped denunciation.

Loudspeakers carried his words to hundreds of tightly packed believers praying in unison in the rabbit warren of narrow streets outside. There, among the angry and unemployed, his tirades fell on fertile ground.

He roundly rejected calls for Western-style democratic reforms, distancing the Islamists from other opponents of the regime, who had been urging then President Chadli Bendjedid to loosen the iron grip of the government on all aspects of life and hold ‘free and fair’ elections.

Ali Belhadj, born in Tunis to parents of Mauritanian origin, was having none of it.

‘Democracy is a stranger in the House of God. Guard yourself against those who say that the notion of democracy exists in Islam. There is no democracy in Islam. There exists only the shura (consultation) with its rules and constraints. … We are not a nation that thinks in terms of majority-minority. The majority does not express the truth.’

‘Allahu Akbar’ (God is greater) chants echoed through the neighbourhood. Who needs political parties when Islam has all the answers, preached Ali Belhadj, who took inspiration from Hassan Al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb, the founders of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood.

‘Multi-partyism is not tolerated unless it agrees with the single framework of Islam … If people vote against the Law of God … this is nothing other than blasphemy. The ulama [religious scholars] will order the death of the offenders who have substituted their authority for that of God.’

In 1966, Qutb was convicted of plotting against Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser and executed by hanging. Hassan Al-Banna was killed by the Egyptian secret police in 1949. Their deaths gave rise to Salafi jihadism, the religio-political doctrine that underpins the ideological roots of global jihadist groups like Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria/Levant (ISIS/L).

As a young journalist with Reuters news agency, I along with other reporters would often go to Al-Sunnah and mingle with the faithful, hoping to gain some insight into the growing under-swell of protest movements sweeping across the region.

Little did we appreciate that we were among those who a few years later would have happily slit our throats. We journalists were not completely correct in assessments of what was going on underneath the surface of such societies, but we were much more in tune with developments than most. Diplomats, regional experts, independent analysts rarely visited such places and totally misrepresented the situation.

The Islamists were dismissed as a minority, religious zealots on the fringes of mainstream society. Events on the ground told another story.

Lawyers, teachers, nurses were all in the movement. They were all virulently opposed to corrupt and incompetent cabals that ran the government and hated security services. Above all, they shared a vision of a better future — grounded in a belief in good governance, moral rectitude, respect for traditions. The deeply unpopular Marxist-influenced government was an ally of the Soviet Union, Afghanistan’s oppressors. The United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) unleashed the Islamist genie from the bottle to defeat the Soviet Union.

Much later, it was therefore no surprise when the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS), created by Ali Belhadj and fellow firebrand imam Abbassi Madani to fight promised elections — despite the distaste for democracy — went on to win Algeria’s first and to date only free and fair elections in 1991, having already swept the board in local polls two years earlier.

The Algerian government panicked. The decision to annul those elections, institute military rule and ban the FIS triggered a decade of violent civil war. Those misguided decisions are directly linked to the current insurgency in the Sahel, the greatest security threat facing Western Europe today and are in danger of being repeated again.

Return of “The Afghans”

Those signing up for the Afghan resistance were not all fighters. Some would work as volunteers — primarily teachers and social workers — in the sprawling Afghan refugee camps near Peshawar, the elegant border town in northwest Pakistan at the opposite end of the desolate Khyber Pass leading to Afghanistan. Their salaries were often paid by Islamic relief organisations flush with cash from US ally, Saudi Arabia.

There, the idealists mingled with other activists of political Islam from Egypt, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Yemen, Kurdistan and Bosnia. For the first time, the countries of North Africa were linked to the Muslim countries of Southeast Asia in what has been described as a great “Open University” of radical Islam.

‘Afghanistan was like a university which introduced a new ideology and school of thought. The ideology of Jihad resistance. It was a gathering point for all the armed resistance. The Islamic movement was going through a renaissance, and all the Islamic schools met each other for the first time and made it like a university, an open room for discussion. For nearly ten years,’ said a former fighter who was there.

One notion which was very quickly rejected was that of “democratic Islam.” The Arab fighters found they could triumph with force. They beat the Soviets, who finally withdrew from Afghanistan in February 1989. Pure unadulterated Islam had triumphed—the lesson was clear.

Others, who did not fight, gained experience with computers and communications equipment, and even absorbed lessons from translated Western manuals on how to combat terrorism, building up a reservoir of skills, which would later hugely benefit Islamist terrorist groups.

The repressiveness and total incompetence of most of the governments of the Muslim world provided sufficient political motivation for Arab Islamist movements, but the evolution of the Afghan war into a jihad for Muslims across the Islamic world moulded them into a global network. And, for the first time ever, the major non-Islamic powers were not — at least initially — in opposition.

Without Soviet support, Kabul fell to the Mujahideen in 1992. The United States decided it was time to reduce, if not eliminate, the Arab presence. Under pressure, Pakistani and Afghan security services began to make mass arrests, aided by the intelligence services of Arab countries keen not to see these dangerous nationals return.

Many fighters drifted away — especially when the Afghans turned on each other. Once again, it was in Algeria where the return of the Arab Afghans was most pronounced. Seasoned veterans, such as Tayeb Al-Afghani, Jaafar Al-Afghani, Abdelhak Layada, Abu Abdallah Ahmed moved quickly into top political and military positions in the FIS and dominated the Armed Islamic Group (GIA), its hardline military offshoot set up after the 1991 election results were annulled.

GIA was led by a succession of emirs (commanders), who were killed or arrested one after another. Unlike the other main armed groups, the Armed Islamic Group (MIA) and later the Islamic Salvation Army (AIS), the GIA sought not to pressure the government into concessions but to destabilise and overthrow it and to ‘purge the land of the ungodly’ — the lesson of Afghanistan had been well learned.

Its slogan inscribed on all communiques was: ‘no agreement, no truce, no dialogue.’

The group employed kidnapping, assassination, and bombings, including car bombs and targeted not only security forces but also civilians. Between 1992 and 1998, the GIA militants, dubbed ‘Les Afghans’ (The Afghans) by terrified citizens, conducted a violent campaign of civilian massacres, sometimes ruthlessly wiping out entire villages deemed unsympathetic.

It also killed other Islamists who had left the GIA or attempted to negotiate with the government. It targeted foreign civilians living in Algeria, slitting the throats of monks and nuns and other expatriate workers. The group established a presence outside Algeria, in France, Belgium, Britain, Italy and the United States, and launched terror attacks in France in 1994 and 1995 — laying the network for later ISIS sympathisers.

However, by 1996, militants were deserting “in droves”, alienated by its execution of civilians and other Islamist leaders. In 1999, a government amnesty law motivated large numbers of jihadis to “repent”. The remnants of the GIA proper were hunted down over the next two years, leaving a splinter group, the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC), which announced its support for Al-Qaeda in October 2003.

During this time, Belhadj, Madani and hundreds, if not thousands, of fellow leaders and followers were in prison. They were finally released in March 2006 under the Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation — effectively an all-inclusive deal ending Algeria’s civil war with compromises between more mainstream Islamist groups, the authorities and other civil society groups.

By now the disillusioned and hardline remnants of GSPC had morphed into Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and would find more fertile territory to the North, where governments were locked in struggles with secessionist Tuareg groups, bandits and homegrown Islamist rebels.

Belhadj’s own 23-year-old son, Abdelkahar Belhadj, was a high-ranking senior leader in AQIM. He was shot dead along with three would-be suicide bombers and two of his associates by Algerian security forces in July 2011 while planning a suicide bombing at a military checkpoint in Algiers.

The Impact of Libya

The Sahel, home to some of the world’s poorest countries and weakest governments, has long been a region of instability. Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso faced ethnically based insurgencies, largely resulting from exclusionist and corrupt governance. They were ripe for radical Islamist influence.

Now, however, just as in Afghanistan two decades earlier, the actions of the West were to give young Islamist radicals a huge helping hand.

In February 2011, as the Arab uprisings swept across the Middle East and North Africa, young Libyans inspired by the crumbling of regimes in Egypt and Tunisia used social media to organise a “Day of Rage” against Muammar Gaddafi’s brutal rule.

The West, led by France, intervened, bolstering the popular uprising. NATO jets soared overhead. Gaddafi was overthrown, captured and killed by insurgents.

Then US president, Barack Obama, said in 2016 that his ‘worst mistake’ was ‘failing to plan for the day after’ in Libya. Current US President and then Vice-President, Joe Biden, opposed the intervention, questioning — correctly as it has turned out — if the West was simply not creating a new “petri dish” where extremism could flourish.

As Biden predicted, Libya spiralled into disarray. ISIS gained a foothold, its first outside of Iraq/Syria and briefly carved out a degree of control over some coastal cities. They were eventually driven out of Libya, but drifted northwards and, importantly, remained embedded in lucrative people trafficking and smuggling rings.

A decade later the price of Gaddafi’s chaotic overthrow is being paid: in migrant deaths in dinghies on the Mediterranean Sea, slave camps on land, the growth of new warlords and crime syndicates and the near total collapse of security across the Sahel.

It is difficult to keep track of all the foreign actors now providing military and financial support to Libya’s factions. Currently, the scene is dominated by Turkey and Russia, as well as the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, and France, and to a lesser extent, Qatar and Saudi Arabia.

The Gulf states, which have historical links with North Africa, are acutely aware that an unstable Libya affects the rest of the sub-region.

Furthermore, the “Arab Spring” and subsequent fall of authoritarian regimes in North Africa has worried Gulf monarchies as the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood and other radical groups could in time threaten their own internal stability.

As a result, the Gulf states – no lovers of radical Islam despite accusations they have turned a blind eye to its export – have lately assumed a much more proactive role in this region. Although this is by no means just a contemporary development, Sub-Saharan Africa is a region in which the Gulf states are now investing politically and economically.

Given waning US interest and influence in Libya and the greater Sahel, the Gulf states have felt compelled to assume a more proactive role in regional affairs and improve their international standing. Given the geographical and cultural proximities, the Sahel has emerged as a prime site for them to form strategic alliances and pursue Gulf interests.

Gaddafi’s fall was the push nascent insurgencies in Burkina Faso, Niger and Mali needed to burst open. Libya’s anarchy and lawlessness fanned the fires smouldering under the region’s corrupt, ineffective and authoritarian governments.

The return of hundreds of combatants, who had served as pro-Gaddafi mercenaries, to Mali and Niger contributed significantly to the destabilisation of the Sahel region. Mali had witnessed numerous rebellions over the years, but it was fighters — both separatist Tuareg rebels who once worked for the Libyan dictator and jihadis — armed with Gaddafi’s weapons that finally captured northern Mali.

France intervened in 2013 and was widely applauded for liberating Timbuktu, which has become the centre of a brutal jihadist rule. France has been involved in the region ever since — heading the counter-terrorism Operation Barkhane, which has stood largely alone against the rising level of violence and insecurity.

In 2017, AQIM merged with Macina Liberation Front, Ansar Dine and Al-Mourabitoun to form the umbrella grouping Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM). Those groups work together and cooperate with new ISIS affiliates as well as with other armed groups of rebels and bandits.

Insecurity Spreads Across Sahel Region

In June 2020, France announced its forces had killed the leader of AQIM, Abdelmalek Droukdel, an Algerian considered to be France’s number one enemy and mastermind behind the 1995 terrorist attacks in Paris, now seen as the official start of a wave of home-grown terror attacks. In September, Macron announced ‘another major success,’ saying French forces had eliminated the leader of Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, Adnan Abu Walid Al-Sahrawi.

But despite these successes, jihadi groups have embedded themselves deeper and deeper into the region and turned large swathes of Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali into ‘no-go’ areas for the authorities. With France threatening to disengage, there is a real fear that the Islamists will gain more advances and link up with other African-based groups.

2021 was the most violent year in the past decade for the three countries in terms of events such as terrorist attacks and battles, with 2,426 such incidents, compared with 244 in 2013, according to data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

In terms of fatalities, it was the second deadliest after 2020, with 5,317 deaths across the three countries, compared with 949 in 2013. Mali alone recorded 948 violent events in 2021, against 230 in 2013. France has also lost some 53 members of the armed forces.

A United Nations mission, in which the United Kingdom has a 300-strong contingent, has also proved largely ineffective despite – at 14,000 — being the world’s biggest peacekeeping force.

Paris has, for years, tried to internationalise the counter-terrorism effort in the Sahel, but with little success, although the US does provide surveillance and intelligence. And, MINUSMA, the UN stabilisation mission in Mali, provides logistical support.

In November 2021, under pressure to cut back its role, French President Emmanuel Macron started to withdraw forces in line with a re-election campaign pledge to cut the 5,000-strong force by half.

To take over, France has created the Takuba Task Force, consisting of special forces from Estonia, Portugal, Sweden and other European countries. It hopes the G-5 Sahel group — composed of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger — can be integrated in some form as it is now widely accepted that support for the Islamists has flourished in part because of an incompetent response by the region’s governments. National armed forces have been accused of killing innocent civilians, eliminating political rivals, and harassing local populations during botched crackdowns on alleged militants.

ISIS has reemerged in the form of the Islamic State in the Great Sahara (ISGS). The latter is responsible for a major increase in attacks by motorbike riding gangs of youths in the so-called “three border” zone where Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger meet. ISGS, JNIM and other groups are in competition but some elements also cooperate.

To the East, Chad, a French ally long seen as the main bulwark against the jihadist threat, also has its own problems with jihadist violence in the Lake Chad region that borders Niger, Nigeria and Cameroon.

Former Chadian President Idriss Déby was killed last April by a rebel group which swept across the country from a safe haven in Libya and the country has had to reduce its commitment to the Sahel force.

Western powers had considered Déby their most important ally in the fight against Boko Haram and now face the nightmare prospect of more link ups between Islamist extremists across Africa. Other well-armed groups professing allegiance to ISIS are now active in Congo, Mozambique and Somalia.

‘It appears Africa is rapidly becoming the epicentre of armed Islamist activity and abuse. In the Sahel, these groups have overwhelmed the region’s armies and fed on challenging geography and weak and often corrupt governance,’ Corinne Dufka, Sahel director at Human Rights Watch, recently told The Times of London.

According to her, these groups had cleverly exploited ethnic, economic and religious lines to garner more recruits. ‘The countries and their international partners should address head on the issues that have underscored decades of instability and opened the door to abusive armed groups: weak governance, rampant corruption and security force abuse, compounded by global warming and population growth,’ Dufka said.

Jihadists Target Coastal States

France is now warning that the jihadist groups in the Sahel are planning to expand their influence to other countries in West Africa, notably Benin and Ivory Coast (Cote d’Ivoire), so as to gain all important coastal footholds and secure their supply lines.

In a rare public appearance in February 2021, Bernard Emié, Head of the General Directorate for External Security (DGSE), revealed intelligence purportedly showing a meeting between top AQIM commanders.

‘The agenda of this meeting was the preparation of a series of large scale attacks against military bases,’ said Emié in the speech at the Orléans-Bricy Airbase. ‘This is where leaders of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) devised their expansion plans for the countries of the Gulf of Guinea,’ he added.

Ivory Coast suffered an attack in 2016, when three gunmen opened fire at a beach resort in Grand-Bassam, killing 19 people. Benin was the scene of an attack against a police station in February 2020, and the kidnapping of two French tourists and a local guide from Pendjari National Park in May 2019.

Emié’s appearance in public was a sign of how seriously the French authorities are now taking the challenge of jihadist groups in Africa.

He confirmed that they had intelligence showing that the jihadists, flush with cash from kidnapping ransoms and gold mining in Burkina Faso, are financing fighters and sending them southwards towards Ivory Coast and Benin, where a deeply corrupt and unpopular government has banned all opposition.

Fighters have also been sent to the borders of Nigeria, Niger and Chad, where groups linked to Boko Haram operate. It seems the jihadists are one step ahead of the West yet again.

Images displayed during his speech supposedly depicted a meeting of top Al-Qaeda commanders — jihadists Emié accurately described as the ‘spiritual sons’ of Osama bin Laden.

The meeting involved Iyad Ag-Ghali, a rebel Tuareg leader and Head of JNIM, who Emié said was now France’s number one enemy in the region. The get together held in February 2020 before NATO’s departure from Afghanistan was captured in a video shot in central Mali by a source, who shared it with the DGSE. The Afghanistan pullout has given the jihadist groups a huge boost with some reporting a fresh surge in new recruits.

Conclusion

It is not too late to meet the threat posed by radical Islamists in the region, but Europe needs to forge a united response around a reinvigorated French leadership and not repeat the mistakes, which led to the Algerian civil war and ended in the ignominious departure of NATO countries from Afghanistan.

The United Kingdom must play its part. It needs to move on from petty Brexit squabbles over fish and migrants and forge a new strategic alliance with France. The United States is not going to play a role other than that of continued logistical support, but this offers an opportunity for Europe.

The crisis in Libya must be addressed, especially since Russia and Turkey are now involved.

The Islamist groups are not as united as it may appear. The lessons from Algeria are clear: moderate Islamists can be accommodated within wider civil society, particularly when historic ethnically based grievances are also tackled. Greater efforts must be made to tackle and dismantle criminal networks, particularly human trafficking gangs, which further undermine security and provide sources of income for extremist groups.

Several insurgents are motivated primarily by local issues and are open to dialogue. Any international force must not simply be used as a means to keep unpopular and authoritarian governments in place against the wishes of their people. Human rights abuses and poor governance by Western allies cannot be tolerated simply because they claim to be fighting jihadists.

However, failure to learn the lessons of the past 30 years will present Europe with a new Afghanistan within sight of its southern flank and provide home-grown terrorists with a safe haven from which to launch more deadly attacks on European soil. It also threatens much of the rest of Africa with risks of a new migration towards Europe.

Resources

- Clayton, Jonathan, ’Jihadists across Africa boosted by Taliban’s victory in Afghanistan,’ The Times of London, 23 August 2021, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/jihadists-across-africa-boosted-by-talibans-victory-in-afghanistan-b2r0lx83z.

- Fethi, Nazim, ‘Al-Qaeda confirms Belhadj death,’ Magharebia, 3 August 2011, https://web.archive.org/web/20120407032749/http://www.magharebia.com/cocoon/awi/xhtml1/en_GB/features/awi/features/2011/08/03/feature-02.

- Financial Times, ’Western concern rises over Sahel militants,’ Financial Times, 10 May 2012, https://www.ft.com/content/1169b398-993a-11e1-9a57-00144feabdc0.

- France24, ‘French troops kill leader of Islamic State group in Sahel, Macron says,’ France24, 16 September 2021, https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20210915-french-troops-neutralise-leader-of-islamic-state-in-the-greater-sahara-macron-says

- Huband, Mark. Warriors of the Prophet: The Struggle For Islam. Basic Books, 1999.

- Human Rights Watch, www.hrw.org.

- Kepel, Gilles. Jihad: The Trail of Political Islam. Belknap Press, 2002.

- Le Figaro, ‘La DGSE dévoile la vidéo d’une réunion de l’état-major d’Al-Qaïda au Maghreb islamique,’ Le Figaro, 3 February 2021, https://www.lefigaro.fr/international/la-dgse-devoile-la-video-d-une-reunion-de-l-etat-major-d-al-qaida-au-maghreb-islamique-20210203.

- Meredith, Martin. The Fate of Africa: From the Hopes of Freedom to the Heart of Despair. Public Affairs, 2005, p. 453.

- Pérouse, Marc-Antoine, ‘France’s fiasco in the Sahel,’ Le Monde Diplomatique, October 2021, https://mondediplo.com/2021/10/03mali.

- SITE Intelligence Group, ‘Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM),’ https://ent.siteintelgroup.com/index.php?option=com_customproperties&view=search&task=tag&tagName=Groups:Al-Qaeda-in-the-Islamic-Maghreb-(AQIM).

- The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, https://acleddata.com/dashboard/#/dashboard